The year is 2016 and tremendous violence continues to be perpetuated by people who seek to impose their reality on others by force. More extreme forms include hate crimes, terrorist attacks, acts of domestic violence, and religious or government policies to stifle cultural difference. Although most people would oppose on principle such overtly hateful forms of “othering”, seemingly minor and often unconscious acts of prejudice and micro-aggression are the ground in which violent extremism germinates and takes root. As we continue to grapple in the United States and elsewhere with painful legacies of racism, sexism, religious intolerance, and other forms of bigotry, one way to participate in necessary cultural healing is to bring greater awareness to these subtle habits of objectifying and demeaning others as they live in ourselves and those closest to us.

Let me be clear; noticing difference is not a bad thing and is not the same as objectifying others. Basic cognition and memory, human or otherwise, is largely organized around the principle of pattern recognition. Our identities hinge upon our ability to distinguish familiar people and surroundings from new encounters. Noticing difference is based in part on biology and essential to our survival, which means it’s a losing battle to try to see everyone and everything as the same even if this were somehow desirable. And yet the ways in which we ascribe meaning to the differences we notice can run the full spectrum from passionate celebration of diversity to subtle objectification or outright violence. Here’s one way to frame the challenge: How can we harness our innate tendency to notice difference in ways that encourage cultural healing rather than harmful othering, prejudice, and violence?

Remember that objectification and harmful othering are not new human problems. Widely diverse cultures have well-documented histories of tearing down the image of local community members or neighboring peoples as a precursor to acts of violence. Fortunately, this means that many of our ancestors have already been grappling with problem of how to temper the human tendency to objectify others, and in some cases this ancestral wisdom remains available in the form of traditions and practices. As a life-long student of world religious systems and doctor of psychology, I’m interested in the strategies that deeply rooted spiritual traditions employ for navigating what I think of as “sacred difference”. Have you already experienced religious or spiritual systems that help you to understand and respect diverse types of people? More than any other single influence, my experiences as a practitioner of traditional Yorùbá religion, also known as Ifá/Òrìṣà tradition, has helped me to expand my vocabulary for diverse human experiences and to take a more kind and informed approach to making sense of and navigating personal differences.

What are Your Taboos? Before exploring Yorùbá perspectives, notice what associations the concept of taboo carries for you. The word enters English from Tongan culture and implies a cultural limit, perhaps rooted in sacred or spiritual realities. Are there any taboos you already honor as part of your religious or spiritual practice (e.g., avoiding certain foods, fasting certain days)? Taboo often carries negative associations such as shaming, restriction, and unkind moralizing. See if you can try on a value-neutral meaning that’s more about the affirmation of personal and cultural limits. We are all unique people with specific cultural settings.

As a European-ancestored American, I know I wasn’t raised with a sacred context for taboo, but I’ve come to see many moral debates through the lens of hashing out cultural-level taboos. For example, most Americans would decline to eat even a gourmet preparation of horse or dog and would also consider such foods to be culturally taboo. Many feel similar about families with multiple husbands or wives, although such arrangements are common in other cultures and among some Americans. Contentious social issues like the death penalty or abortion tend to hit people on the gut level of cultural taboo. If you’ve lived in other countries or reflected on cultural difference, you likely understand that communities and cultures are formed in part from an intricate system of do’s and don’ts.

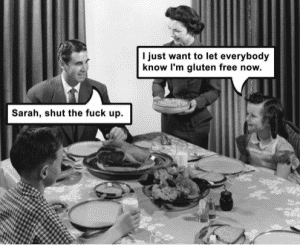

In addition to widely held societal or cultural taboos, most Americans are willing to respect personal differences when it comes to food, drink, and intoxicants. When feeding friends and family who are vegetarian, lactose-intolerant, or who have food allergies, most cooks understand that some foods we enjoy are harmful, effectively taboo, for others. We also tend to respect the choices of those we love when they decline to drink alcohol or share in a smoke break. And folks with allergies, food sensitivities, or a preference for sobriety may also experience pressure, judgment, and variable levels of accommodation around personal difference.

Taboo (Èèwọ̀) in Yoruba Culture. One of thousands of differently beautiful indigenous African cultures, Yoruba culture is the root of Ifa/Orisa tradition, now the most widely practiced indigenous African system on Earth. Millions of devotees practice diverse lineages of the faith in West Africa (e.g., Nigeria, Benin, Togo), the Americas (e.g., Brazil, Cuba, Trinidad & Tobago, United States) and beyond. Over the past decade I’ve been blessed to participate in lineages of Ifá/Òrìṣà tradition both in the United States and Nigeria. In the past four years I’ve made pilgrimages to Ogun State, Nigeria to undergo initiations to Ifá, Ọbàtálá, Ọ̀ṣun, and Egúngún in the lineage of Olúwo Fálolú Adésànyà Awoyadé from Òdè Rẹ́mọ. This means I am a beginner in my training (ọmọ awo), and it’s as a non-Yoruba, American initiate that I share on a basic teaching familiar to practitioners of any lineage of the larger tradition.

Èriwo or èèwọ̀, usually translated as taboo, plays a key role in Yoruba traditional religion. Taboos may be temporary or life-long and may pertain to food and drink, clothing, behaviors, personality/character traits, ritual actions, etc. For example, like some other Ifá initiates I have a taboo against wearing black or red clothing, betraying confidences, or failing to respect my elders. Based on the outcome of divinations during my initiation, I also have life-long taboos around certain foods and behaviors. Lifetime taboos are commonplace for initiates and range from hardly noticeable to life altering. One assumption about taboo is that because each person’s destiny is a bit different, each person has a distinct formula or recipe for success when seeking to fulfill that destiny here on Earth. Different destinies give rise to different taboos.

When folks consult with an Ifá or Òrìṣà priest, they often receive temporary taboos based on divination outcomes. For example, after a reading you could be asked to avoid wearing patterned cloth, to abstain from eating coconut, or to decline to host guests in your home for a few months. Insofar as the deities or oriṣa are also players in the larger ecology of reality, they also have taboos. Ram may be offered to Sàngó but not to Ọya. Hen may be offered to Ifá and Ọ̀ṣun but not to Ògún. Dog may occasionally be used to feed Ògún but not Yẹmọja. Palm oil is beloved to Èṣù but not typically given to Ọbàtálá. Like human beings, the deities have personalities and preferences as well as things that are distasteful or even problematic for them.

In this context I’m concerned with how Yoruba teachings on taboo and sacred difference can shed light on a blind spot in modern American culture around what I’ll call personal character or behavioral taboos. To clarify how personal character or behavioral taboos differ from widely shared cultural taboos and from the more familiar category of personal food and drink taboos consider the following examples. Some receive a taboo against jumping in to rescue people, while others in the same tradition walk with a taboo that discourages them from declining to help when asked. One divination signature comes with a taboo around arriving late while another carries a taboo on punctual arrival. Some receive the guidance that prosperity will come from living and working close to home in inherited professions while Ifá admonishes others to travel and innovate for success. Ifá counsels some to mediate disputes or speak out as catalysts for justice, while others receive taboos on getting too immersed in conflict, participating in protests, or speaking from a place of anger. Some are encouraged to have dogs as pets or raise animals for food while others have taboos on both. The tradition easily recognizes thousands of specific short and long-term guidelines that could be classified as personal-level behavioral or character admonitions and taboos (do’s and don’ts). Remember taboo is linked to the view that we have unique destinies to fulfill here on Earth, and therefore we each have a litany of things that can support or hinder us in that undertaking.

What if some of our avoidable interpersonal strife arises from the lack of a framework for respecting and even celebrating our different temperaments and paths of destiny? When we fail to proactively appreciate personal-level diversity, including within the same family and cultural group, we tend to fall back on the guidelines available to us; either believing that everyone should follow our cultural norms and/or that everyone should do what happens to be personally best for us. In either case, odds are high for miserable interpersonal outcomes. In contrast, Ifá/Òrìṣà tradition, like many other indigenous paths, affirms that life is not a one-size-fits-all situation and not everyone needs the same things to be happy and living their purpose.

Honoring Sacred Difference in Everyday Life. If we try on the view that we each have unique, personal destinies and that these soul-level differences give rise to somewhat different recipes for a successful life, how can we then apply this perspective in our everyday lives and relationships? Knowing that most people will never become involved in Ifá/Òrìṣà tradition or Yorùbá culture, how can a basic understanding of sacred difference benefit people of any background?

1. Cultivate a Vocabulary for Sacred Difference. You probably already have some vocabulary for intrinsic or soul-level difference that accounts for diverse personality traits and behavioral dos and don’ts. For example, many people identify with their astrological sun sign (e.g., Gemini, Pisces, Capricorn) or Chinese astrology patron (e.g., monkey, snake, horse) in part because this provides a non-judgmental language for personal differences. Traditions of numerology as well as more recent systems like the Myers-Briggs Test, the Enneagram, and Human Design speak in similar ways to a natural desire to be seen and welcomed for specifically who we are. Keepers of these and other systems seek to apply their respective vocabulary for sacred difference in ways that improve our personal lives and relationships.

In Ifá/Òrìṣà tradition we recognize hundreds of divine powers or deities; however each practitioner’s religious path and training within the tradition is personalized, again because we each have different destinies. Consider the tradition as a kind of university campus; we don’t all major in the same subject and there may be whole departments and professors with whom we have little contact. People new to traditional Yoruba religion often want to know, “Who is my patron or head òrìṣà?” Although West African lineages of practice may answer this question slightly differently from branches of the tradition based in the Americas, all agree that our path of destiny largely informs which deities or òrìṣà we ideally align in order to bring out our gifts and potential here on Earth. Although I’ve personally found the vocabulary for sacred difference in Ifá/Òrìṣà tradition to be especially nourishing, this is only one of hundreds of lovely intact traditional frameworks. Try to identify as least one map for personal difference that speaks to your mind and heart and then go deep enough into that framework to increase your tolerance and ability to relate skillfully with people who are organized in fundamentally different ways than you. Be able to describe, without judgment, at least eight to ten different types of people and to appreciate something about how they may need different things for their happiness.

2. Try Not to Project Your Personal Settings Onto Everyone Else. This is often more tricky in practice than theory and it’s close to heart of the matter on sacred difference. To first clarify, allowing for personal differences does not mean we abandon universal or core values. For example, I personally hold human rights as defined by the United Nations as a kind of universal truth. Stated another way, in my cultural reality the violation of someone’s human rights is a universal or societal taboo even for people who don’t agree with me. In the United States we have a cultural taboo articulated in the First Amendment of the Constitution against one religion interfering with the free expression of another religion. Although I don’t have the power to enforce this preference, I believe this taboo would be beneficial for all nations to observe. I don’t care if your religion dictates that people of other religions should be treated as less than fully human; I’m not obligated to respect that view. There are times to stand in our understanding of universal truth, including the ways that these views take the form of laws and institutions. Culture is just like that; we advocate, hopefully in constructive ways, for what we believe to be the best shared agreements for everyone to follow. This kind of cultural stance around core values is entirely compatible with proactively preserving considerable space for personal difference.

While we navigate ways that our cultural settings differ within in our families, communities, and nations, considerable personal differences remain among individuals, even in families with strong agreement on cultural values. This is the terrain where having some kind of framework comes in handy, and I believe it’s a weak link in modern American culture. Let’s say you are conflict-averse and diplomatic with lots of watery qualities in your nature and your sibling is direct to the point of being confrontational. Whether it’s because they’re a Chinese Fire Rooster, an 8 on the Enneagram, a child of Shango or Thor, or a Capricorn with an Aries rising: whatever helps you not to judge them for being organized differently than you, go with that. You may still struggle with how they show up in the world, but the extra layer of judgment about who they are as a person is optional and counter-productive.

Another way to temper our tendency to project onto others is to proactively assume that others are not going to share your personal taboos. For example, maybe you’re a person who really needs to trust your first instinct about people and situations. You’ve been burned from getting too analytical and over-riding your intuition. You’ve discovered this truth about your life, and now you know better. A friend asks for your advice on how to navigate a situation. Are you safe to assume that they also need to trust their first instinct? What if it’s just as likely they learned the hard way over the past thirty years that they actually get better results when they don’t follow their first instinct? What if their formula for success includes analysis, dialogue with trusted friends, dreaming on a situation, and methodical deliberation? When we discover what’s best for us it’s often exactly that; incredibly useful information about what’s best for specifically us, no more or less. Another safe assumption is that from time to time we’re just going to project our personal truth onto others in annoying ways; because it’s human, because it’s easy, because we’re excited, and because we just get interpersonally lazy. When we realize we’ve done this, we can course-correct, name with humility what we believe has happened, and apologize or make amends when possible.

3. Assume Others Know Themselves Better than You. Even if you’re relentlessly full of judgments and opinions about others and how they ought to be, you can still cultivate a simple but potent habit of perception that I like to think of as “making space”. By that I mean intentionally holding in your awareness the physical, emotional, and spiritual space for others to exist as genuine sources of wisdom, surprise, and new data about reality. For me this looks like noticing my first reaction without letting it dominate my awareness, pulling back my energy and attention in a more contained way, and holding a stance of openness and curiosity about the beings, human and otherwise, with whom I come into contact. This respect for personal space, autonomy, and difference is more or less the opposite of pressuring others to be like you or to agree with you.

When I make space for others, I often notice they’ve been reflecting on their life and conditions well before meeting me. Sure, I occasionally notice things about people that they don’t see about themselves (and vice versa), but more often I find that people have some insight into who they are and what they require for their happiness. Chances are you’ve noticed the difference between people holding a kind and curious space for your experience and, in contrast, people hogging all the space, and letting you know what’s best for you. You don’t enjoy that second experience so why serve it up to others? Chances are you already see yourself as one of the respectful people who does a good job at making space for others, but how sure are you that you consistently extend this gift of presence? I know this is something I need to constantly work at, and based on the amount of unsolicited advice I receive, I know I’m not the only one.

A gentler way to approach the reality that you may have useful perspective to share with others is to begin with curiosity about how they already see a situation. “I notice you seem to struggle with such-and-such situation, and I wonder if you’d like to help me to understand how that is for you or what you’ve already found to be helpful.” Until we can listen with openness to the perspective that others already have about themselves, we may not be ready to give advice, and instead we run the risk of simply projecting our personal settings onto others. Remember: If we have different destinies, we also have different formulas for success. Your enthusiasm at discovering your formula does not necessarily translate into benefit for your sibling or neighbor and may even cause you to become an annoying person. By cultivating a habit of spacious, open-hearted listening, others will tend to feel seen and appreciated in their diversity, and your appreciation for differently beautiful ways of being will naturally increase.

People of any background can cultivate these and other simple habits of awareness that harness our tendency to notice difference as a celebration of beauty and diversity rather than fuel for subtle or even overt aggression. I give thanks to the rich and varied religious and spiritual systems that provide guidance for respecting and navigating sacred difference. These systems are precious ancestral legacies with medicine for modern troubles, and I gently encourage practitioners of all faiths to bring forward teachings that help devotees to more skillfully navigate our beautifully diverse modern world.