Translation and author reflection in Mandarin.

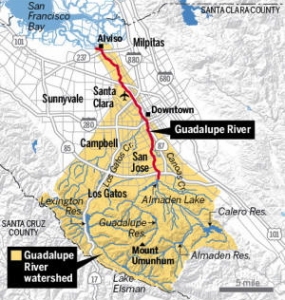

In early January 2009, I guided a dozen or so practitioners of diverse earth-honoring paths in a year of healing and honoring ceremonies focused in the Guadalupe Watershed. At the far southern end of San Francisco Estuary, the 170-square-mile drainage of the Guadalupe River includes the site of the most productive mercury mine in United States history, a sacred mountain for the Ohlone people (Mt. Umunhum) whose summit is still off limits due to lead and asbestos toxicity, dams on all creeks of any size, and nearly a million largely urban and suburban South Bay residents. In recent decades practitioners of earth spirituality have focused relatively less ritual work in the Guadalupe watershed than more frequented Bay Area sites such the East Bay hills, Mt. Tamalpais, or the city of San Francisco. Our circle began with the shared understanding that our efforts to establish trust and dialogue with the spirits of place in this historically desecrated watershed may require patience, tenacity, and abundant heartfelt offerings.

The twenty or so gatherings that followed brought about more magic and beauty from our weaving with the land than any of us could have imagined. The mining history of Alamden Quicksilver County Park in combination with nearby Mt. Umunhum, a sacred peak desecrated by a toxic, abandoned Air Force Base, served as opportunities for participants to learn to co-create rituals of earth healing and repair in an area of human abuse and neglect. Our core circle convened once a month for a full day of ceremony, and we complemented these monthly gatherings with open community events like river clean-ups, purification lodges, and native plant restoration events.

We spent the first half of the year in the highlands on and around Mt. Umunhum and the second half winding our way along Los Gatos and Guadalupe Creeks, through downtown San Jose to the Guadalupe River, and eventually out Alviso Slough near San Francisco Bay. Before each day-long circle, one or more of us walked the land, listening for guidance about what would be welcome and supportive to the spirits of place in the gathering to follow. We then brought these messages back to the larger group to assist us in preparing for that month’s ceremony. During our gatherings, we sang, drummed, prayed, cleaned up trash, made offerings to and engaging in visioning with the spirits of the land, shared personal stories and dreams, and sometimes established natural shrines to anchor and amplify various healing intentions.

At the heart of our tending in the first season of the year was New Almaden Quicksilver Mine just south of San Jose. The site of the largest mercury mine in North American from the 1850’s until the 1970’s, New Almaden saw the extraction of nearly 85 million pounds (over 40,000 tons) of liquid mercury and the carving out of over 45 miles of mining tunnels. The mercury was primarily used to separate gold from its corresponding ore during the Gold Rush and in this way the mines at New Almaden came into being through a hunger for wealth that was also tremendously destructive for the Native peoples and the Holy Earth in other parts of California. Over a century later the entire Bay Area ecology, from human beings to microorganisms, continues to feel the effects of mercury pollution, and the Guadalupe River remains the single greatest source of mercury entering San Francisco Bay.

After spending a day in January on Mt. Umunhum along the upper Barlow Rd trail presenting offerings to the mountain and seeking guidance for the year, we then spent two full days in February and March at Almaden Quicksilver County Park, specifically on Mine Hill, an epicenter of past mining activity. In February we offered a full day of healing and honoring ritual for the human ancestors of place, specifically for those who died in mining accidents or mercury poisoning. This also included paying respect to indigenous Ohlone ancestors whose rich cultures and ways of life were profoundly disrupted from Spanish arrival in the 1770’s through the entire Gold Rush period and beyond. In March we returned to present abundant offerings and ritual apology to the other-than-human spirits whose bodies are the land there (e.g., water beings, plants and animal relations, spirits of metals, other nature spirits, and the Earth as a collective presence).

Both days of ceremony revolved around a Mongolian-style oboo or world mountain shrine (see the work of Sarangerel Odigan) consecrated together in February at Mine Hill. One intention anchored at the shrine was to ask the spirits of place to aid in healing addictive energies, including those of the type that fuel gold and mercury mining. We made intent to release addictive patterns in our own lives and placed a stone with other offerings to feed the work of transformation. The shrine has been visited and renewed/reconstructed, always with offerings (e.g., honey, tobacco, spirits, spring water, colorful prayer ribbons, food offerings) for the local powers.

The rituals at Almaden were demanding in that we attempted in a short amount of time to establish a ritual anchor/shrine that could continue to feed the natural energies and be easily re-energized during subsequent visits. Once consecrated, the oboo seemed to function by providing a physical manifestation of the world center that could receive offerings and focus our modest efforts toward shifting the energetic balance at this place of historic desecration. From this opening season of rituals the rest of the year flowed relatively easily with a sense of synchronicity and increasing trust and interest from the spirits of place. The year series was particularly satisfying in that our gatherings occurred in a fairly concentrated area (the Guadalupe Watershed), we were able to include regular prayers in a Lakota-style purification lodge (inipi) led by a friend and sun-dancer in Los Gatos, and we also complemented the ritual work with several river clean-ups along the Lower Guadalupe.

In the spring we moved further up the mountain for several months of ritual along Upper Guadalupe Creek. At this same time news broke that U.S. Representative Mike Honda of California’s 17th District (including Mt Umunhum) was on the verge of a major breakthrough to secure funding for summit restoration thanks to President Obama’s economic stimulus package. We prayed for good outcomes both with the mountains spirits and in lodge and felt elated later in the year when, after decades of delays, the federal government finally confirmed most of the necessary summit clean-up funds!

The second half of the year brought us to the lowlands of the watershed, mostly along dry creek beds and the concrete pathways of the Lower Guadalupe. We consecrated peace trees for the ancestors of place in Campbell Park and Ulistac Natural Area, offered a despacho ceremony at Convergence Point in San Jose, and continued to lift up prayers in the nearby sweat lodge in Los Gatos. We felt bolstered by the news that summit restoration would begin in the coming years and like we were one small force in the larger reawakening of beautiful, ancient land spirits.

In January of 2010, shortly after the completion of our year commitment I received a very distinct message from the spirit of the mountain. This type of spirit message is somewhat unusual for me as I don’t consider myself particularly psychic or prone to spontaneous demands from the unseen. I was told that I needed to advocate, in writing, for the inclusion of a ceremonial space on the summit of the mountain. Although I felt skeptical about this being well-received, ignorant about the public input process or timing, and unaware of any other public park in the United States managed to include such a feature, I figured I had better give it a try. So, I drafted the letter, reached out to an Ohlone friend for input, and got another 30 or so folks to sign on before submitting the proposal to the director of Mid-Peninsula Open Space Preserve (Mid-Pen), the official stewards of the mountain. In addition to encouraging the inclusion of a ceremonial space in the plan for the restored summit, the letter strongly advocated for inclusion of Ohlone leaders in all decision-making.

To my surprise, shortly after delivering the letter I received a warm and constructive call from agency director Steve Abbors. And to the best of my knowledge Mr. Abbors and Mid-Pen have been true to their word that day about including Ohlone voices in the planning process. And as of September 2015 substantial progress has been made on opening the summit to public access, and all three versions of the final plan still include a designated “ceremonial space”. I don’t presume to know who or what exactly impacted the course of events, nor does it particularly matter. What I do know is that after being off-limits to the public for decades, in the next few years I’ll be able to stand near the summit of Mt Umunhum and offer prayers and praise in a designated ceremonial space. What I also know in my bones is that heartfelt ritual, when approached with humility and cooperation with the elder forces, can literally move mountains.

For more information on the summit restoration process see the excellent work of Mid-Peninsula Open Space on Mt Umunhum. For another excellent organization in service to the land in the South Bay, Guadalupe Watershed, see Ulistac Natural Area. To hear directly from one contemporary Ohlone leader see this interview with Charlene Sul.